Continental Drift: A Tribute to Laurens Tan

Continental drift is the slow movement of Earth’s landmasses. Once fused together, now inching apart over millennia, shaping the world as we know it. It is a quiet force that rearranges geography, carves new coastlines, and redefines connection.

Laurens Tan’s life followed a similar path. Expansive, shifting, and deeply transformative. Born in The Hague, rooted in Chinese heritage, and working between Wollongong, Beijing, Las Vegas, and beyond, Laurens moved through the world with the inevitability of tectonic plates — bridging cultures, reconfiguring boundaries, and creating new ways of seeing wherever he went.

His practice was one of constant translation — between East and West, tradition and technology, humour and critique. Laurens was always in motion, always reshaping the landscape around him. Continental drift personified.

Laurens Tan, Adapt/Enforce, 1992

Wollongong Art Gallery

Though his life was shaped by movement, translation and reinvention, at the heart of it all was Wollongong. This city was more than a backdrop of his peripatetic life. Little old Wollongong was Laurens’ cultural home and a site of lasting impact.

Laurens first arrived in Wollongong in the 1980s, teaching in the Faculty of Creative Arts at the University of Wollongong, where he also completed his Master of Creative Arts. His academic and conceptual grounding took root in Wollongong, and his teaching inspired a generation of local artists and thinkers.

In 1992, Laurens became the inaugural Artist in Residence at Wollongong Art Gallery after it had moved to its current location in the former Council Chambers. This was a pivotal role that led directly to the creation of Adapt/Enforce, one of his most iconic public works, adorning the gallery’s façade. Featuring magnified screws arranged beneath the bold words ADAPT and ENFORCE, the work travelled to institutions such as Queensland Art Gallery and Casula Powerhouse and reimagined for Sculpture by the Sea, but its origins were deeply tied to Wollongong, its steelworks, and its symbolic textures of labour and control.

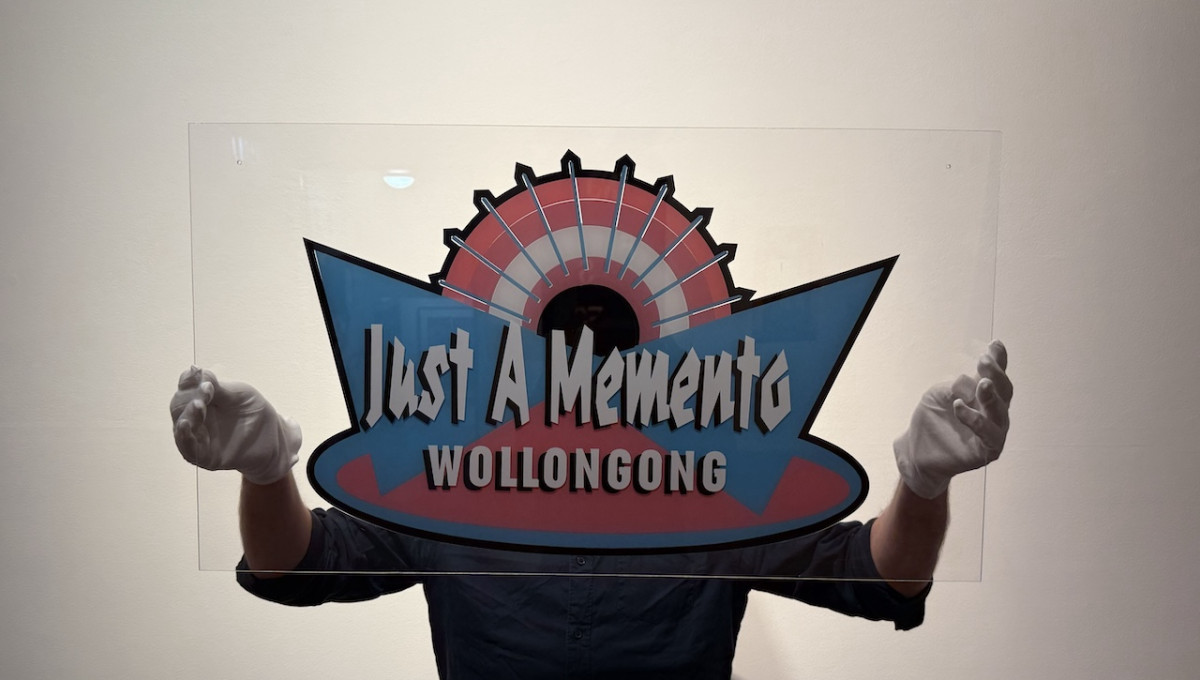

Wollongong was not just a place Laurens lived and worked; it was a community he helped shape. He served on the Board of Wollongong Art Gallery for several years, contributing his vision to the city’s cultural leadership. He also exhibited regularly with Wollongong’s long-running artist-run initiative, Project Contemporary Art Space. Memorable exhibitions including Just a Memento (1995) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1999) reflected his interest in social ritual and cultural inheritance.

Laurens Tan, Just a Memento, 1995

Exhibited: Just a Memento, Project Contemporary Art Space, 1995

Collection Wollongong Art Gallery

Even a suburban Chinese restaurant like Lim’s Café became, in Laurens’ eyes, a symbol of “forged authenticity” — a survival strategy turned cultural artefact. Through his research, Laurens believed Lim’s to be the first Chinese restaurant in Wollongong, with Mars Café in the north of Wollongong following soon after. He salvaged signage from both when they were abandoned and used them in his evocative work Café Curtains — a series of light boxes incorporating restaurant signage paired with actual curtains from suburban Asian eateries. While signage changes, Laurens noted, the curtains often remain — made from the same indestructible materials, quietly carrying the textures of place and continuity. In works like this, everyday sites became visual archives — personal, cultural and collective — telling broader stories of migration, resistance, hospitality and transformation.

One of Laurens’ most sharply satirical local works, Game Theory 1 (2000), was made for a Biennale of Sydney satellite exhibition at Wollongong Art Gallery. Based on his research into theories of risk (particularly the work of John Von Neumann) the installation proposed a provocative idea: What if urban development approvals were decided not by bureaucratic process, but by a game of roulette?

Laurens Tan, Game Theory II, 2000

Collection Wollongong Art Gallery

The interactive work was operated from the original Mayoral Chair of the City’s 1950s Council Chambers, faithfully reconstructed using matching timbers and historical detailing. Laurens embedded imagery of the Illawarra and local heraldry to create a convincing veneer of institutional legitimacy. In doing so, he exposed the arbitrary logic of civic decision making — turning risk into ritual, and ritual into critique to create a truly subversive work.

Placing a work like this in a civic cultural site — a regional gallery once home to the Council Chambers — was itself part of the commentary. It pointed to the precarity of cultural institutions, often starved of adequate support and subject to the whims of government funding cycles. We all know how decisions about arts funding can feel just as arbitrary, and just as powerful in shaping or destabilising the future of an institution.

Game Theory 1 was conceptually rich, locally anchored, and structurally playful. It used familiar objects to question how power operates in public space. Laurens’ work didn’t just observe systems, it infiltrated them.

Laurens Tan, Vegas of Death, 1995-2001

Collection Wollongong Art Gallery

Among the most powerful works to connect Laurens’ ideas about death, design, industry, and spectacle is his installation Vegas of Death, now held in the Wollongong Art Gallery collection. The work bridges two poles of his practice: Wollongong and Las Vegas, the local and the hyperreal. Set in a coffin-shaped arcade cabinet, the piece mimics a Vegas poker machine but uses crematorium imagery – ash hoppers, mortuary signage, disposable coffin fittings – to draw uncomfortable connections between gaming culture and the industrialised rituals of death.

For Laurens, modern cremation symbolised a broader truth: that even our final moments are increasingly shaped by efficiency, logistics, and mechanisation. He saw cities like Wollongong and Vegas not as opposites but as reflections — industries of transformation, whether of coal or culture, steel or souls.

Vegas of Death is visually seductive, full of light and sound. But at its core, it delivers a powerful commentary on how human mortality finds common ground with obsolescence. It reveals how entertainment masks erasure, and how even the deeply personal experience of grief can be commodified by capitalism.

Rue du Plaisir, 1990

Charcoal on paper

Collection Wollongong Art Gallery

Laurens’ sharp observations of migration, displacement and power were not confined to sculpture or installation. His drawing Rue du Plaisir (1990), in the Wollongong Art Gallery collection, feels strikingly prescient today. Created during his residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, the work traces the Statue of Liberty’s origins in France before its arrival in New York in 1886. The title, meaning “Street of Pleasure,” is laced with irony. His charcoal rendering shows not celebration, but the gritty street life of impoverished immigrant hawkers in northern Paris.

In the weeks after Laurens’ death in the United States, as Trump began his new presidential term and a French politician called for the repatriation of the Statue of Liberty, the work’s layered commentary on the symbolism and politics of liberty felt especially acute. Like so much of Laurens’ practice, it collapses history and the present, the ideal and the lived reality, reminding us that migration and displacement are deepening into an ever more urgent humanitarian crisis.

Chicken in a Basket, 2021

Exhibited: Birds and Language, 2022

Curated by Madeleine Kelly

Wollongong Art Gallery

Las Vegas, where Laurens spent much time in his final years and where he ultimately passed, was both his subject and his stage. Vegas, with its simulations, repetition and excess, allowed Laurens to reflect back the contradictions of the contemporary age.

Yet even in Las Vegas, his roots in Wollongong remained evident. The enduring concerns of labour, migration and adaptation in his practice continued to pulse beneath the neon. His art, wherever it landed, was shaped by the questions he first asked in The Gong.

Laurens Tan lived a life in translation: between continents, cultures, forms and meanings. He taught us that art is not a set of answers, but a process of reimagining the world. A way to confront systems, question rituals and imagine new ways to be.

Babalogic, 2008

Exhibited: Zhongjian Midway, 2010

Curated by Jin Sha

Wollongong Art Gallery

By Daniel Mudie Cunningham

Image: Laurens Tan with assistant Tony Mallon, Adapt/Enforce, 1992 Wollongong Art Gallery