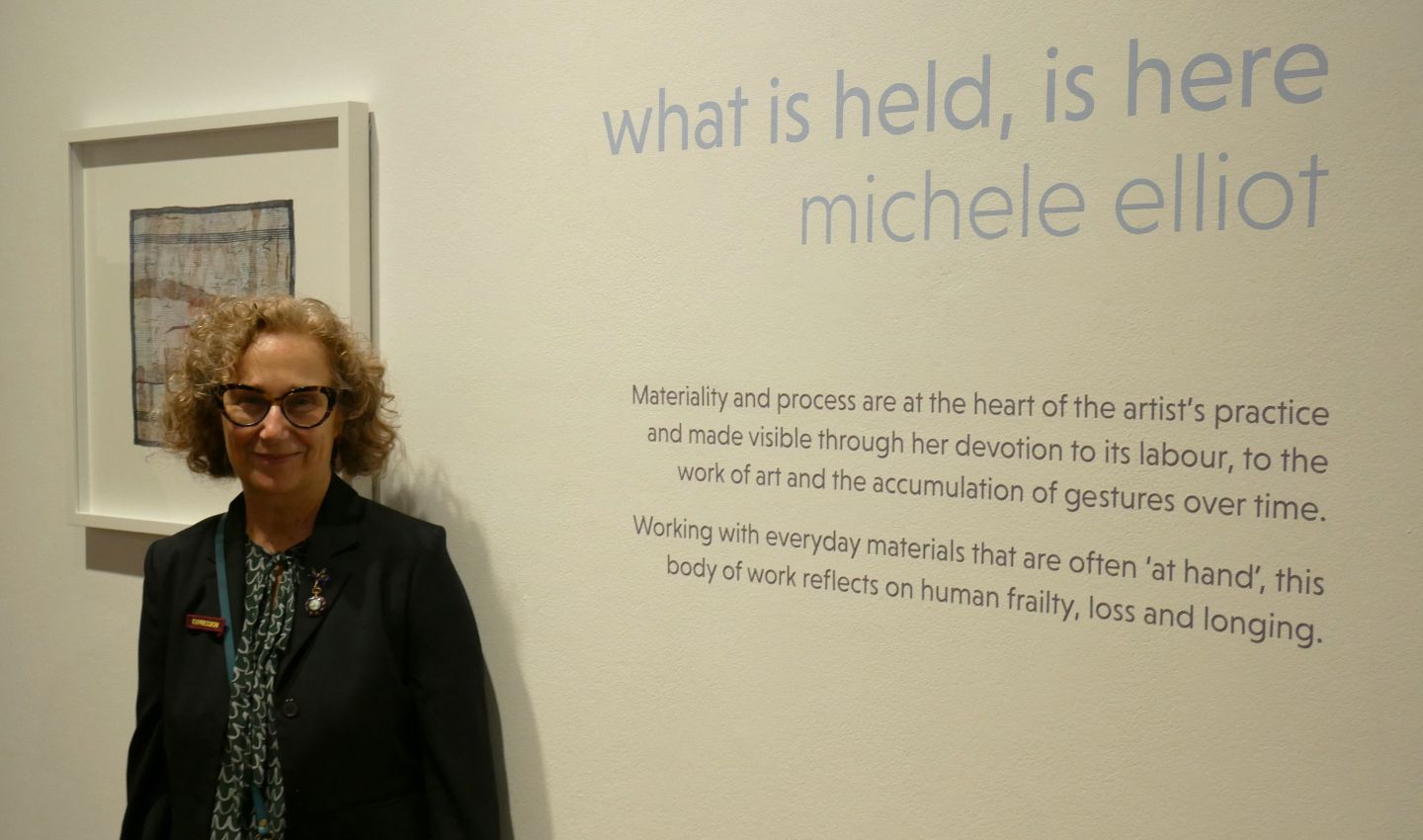

Q&A: Michele Elliot on what is held, is here

Local artist, Michele Elliot is a textile artist working with upcycled and collected materials. Her exhibition of new work titled what is held, is here is on at Wollongong Art Gallery until 25 August 2024.

Materiality and process are at the heart of Elliot’s practice and made visible through her devotion to its labour, to the work of art and the accumulation of gestures over time.

Get to know Michele, her motivation, and her thoughts around death and dying.

Let’s kick this off with our first question. Who is Michele Elliot?

Artist, bird watcher, book lover, card player, collector, cook, gardener, listener, music lover, partner, reader, sister, swimmer, walker, yogini and a writer of lists.

Can you comment a little on your backstory and why you started making art?

My high school art teacher, Frederike Bendler, was a huge influence on my decision to study art. She sparked a deep curiosity in me, particularly regarding history. In a wonderful twist of fate, I reconnected with Rike about twelve years ago. She had retired and was still painting and exhibiting. She came to see my exhibition, whitewash, at Wollongong Art Gallery in 2014, and that meant so much … to be able to thank her, to talk about the work with her. Sadly, she died last year. I was sorry we couldn’t meet and discuss this current show. The soft columns are a quiet nod to her passion for art history, and in particular the architecture of Greece and Rome. Rike came to Australia from Germany as a teenager with her brother and parents. She would have been in her early-mid 20s when she taught us. Rike had a fantastic fashion sense, she drove a green VW Beetle, wore fabulous chunky jewellery and pendants and platform shoes. To us kids in Western Sydney in the 70s, she was chic and cool. A friend and former art classmate recently sent me a link from the National Maritime Museum, where Rike had lodged an archive of her family’s voyage to Australia in 1956. I’m keen to see what it contains.

Later, my parents moved from NSW to WA and there I studied painting and sculpture at Claremont Art School in the late 80s. We had nine hours of drawing each week, what a gift that was. I think drawing underpins so much of my practice even now. Over the years, I have continued with study … a Grad Dip at Sydney College and later an MA at Monash, both in Sculpture. That academic framework is an important one for research and writing, which I’ve come to love.

What are the mediums, processes and techniques that interest you the most and why?

Drawing, and thinking with a drawing hand, a drawing eye, is fundamental. Not so much in a traditional sense but more for the elements and processes that align with a drawing practice. Ultimately, drawing is about observation and discovery. And importantly, about not knowing. Drawing has an immediacy that can be surprising, subtle, powerful. Drawing ‘in the expanded field’ has opened a wide door for artists and I love this. Even though I don’t always pick up a pencil or a stick of charcoal, I try to bring this sense of enquiry to my practice, to working with cloth, clothing, thread, assemblage, sculpture, installation.

I have worked with cloth and clothing since art school, though not exclusively. My first installation she sighed and said, 1988, was a site-specific room constructed from wallpaper and calico, with objects made from paper and a recycled dress collapsed on the floor, it was dyed with yellow paint. A kind of sculptural fiction. Cloth and clothing in its connection to the body, to the human, speaks to the shape of our bodies, to how we are in the world, to the life lived in these garments, to memory, to absence and the passing of time. I’m drawn to working with material that holds meaning and might convey my intentions, or evoke a connection, a possibility for audiences who come to view my work. I always hope that people can find some meaning for themselves, through this kind of material familiarity.

How are you connected to our region and why does community mean so much to you? Can you describe how you think your practice impacts and helps our sense of community?

I came to the Illawarra in 2010. My partner and I had moved a couple of times and on coming back to NSW, wanted to live outside of Sydney and still be close enough for family and work. After several years of teaching in Sydney, I had an experience that eventually led me to change the way I lived and worked. I was walking with friends in Nepal in 2015 when a massive earthquake impacted a vast area of the country and killed ten thousand people. Upon returning home, I made some decisions about changing my work situation, to be more connected with where I was living.

I met Lizzie and Caitlin from The Rumpus (now Makeshift) and began holding community skill share classes with them, and incredibly, began a residency with Tender Funerals. They had received some funding from Create NSW and along with musicians, Jodi Phillis and Malika Reese, we worked with several families to help them find creative expression in their loss. The legacy of this residency continues in the Tender Community Choir, and for me, the fortnightly Sewing Circle I facilitate.

In terms of impact, I think that its more for others to talk about fostering a sense of community.

What I can share is that when I stood in the gallery at the exhibition opening and looked around, it was the first time I’d really ‘seen’ the show. And I also realised just how many people had been beside me in the making of this work over several years. I’ve felt a kind of reciprocity, where I’ve been able to build a connection to our community, in teaching and working on several arts/health projects (working with carers of people living with dementia, a research project on the experience of palliative care, a collective artwork with the staff, students and community at UNSW Library). At the same time, this work has been provided me with a stable foundation and a real sense of belonging.

When did you decide you wanted to undertake ‘what is held, is here’ and what was the driving motivation? And the title, well it is so beautiful. How did you come up with this?

I can thank John Monteleone, Wollongong Art Gallery's recently retired Director, for encouraging me to make a submission for this show. We were at an opening not long after the Covid restrictions were lifted, and he asked if I’d considered applying for a solo show. I’d last exhibited at the gallery in 2014 with whitewash. I really appreciate the deep commitment that the gallery has to artists in our community, so I did put a proposal together.

In amongst all the mayhem and uncertainty and restrictions of the Covid lockdowns, of where we could go and what we could do, I began to think about this as a kind of brief to myself for a project.

So, what if I could only work with what was at hand. I began to make an inventory of my linen cupboard and fabrics, of the material in my studio including a collection of sheets, mostly white, some printed, like big blank canvases, full of possibility.

The title didn’t come until late in the project. With most of my work, I am always trying to find a balance between a kind of openness and poetry, and a link between the process and what the artwork is doing. I want the titles to reflect that too.

what is held, is here is in fact, the title of an essay written in 2018 for the exhibition publication ARTEMIS Remembers. The exhibition was curated by Gemma Weston at the Lawrence Wilson Gallery in Perth. It documented the Women’s Art Collective, Artemis and the essay was based on my thirty-year friendship with WA artist, Jo Darbyshire and our letters and journals.

The words in the title encompass a feeling of being in place, of looking down at my open hands and asking the question ‘well what do I have, what is here, what am I holding’ in the broadest possible sense. And maybe the artworks in this show are asking those questions too, and maybe they are also responding to those questions.

What is your most favourite piece in this exhibition and why is this?

the confidantes series could be my favourite, though it doesn’t feel like the right word. A better one might be ‘beloved’. Mmm, though is it one work?

These are the photographs of embroidered grids on my father’s handkerchiefs. The grid became a kind of calendar, a way of marking time. I have clear memories of him always carrying one. He died in 2000, and I only wanted those twenty-three hankies. I had no idea what I would do with them. When I began the residency at Tender, I had a glimpse of what this project might be. It is always such a sweet moment, when a cluster of thoughts come together, and a work begins to surface.

The other important component of the confidantes was the collaboration with twenty-two women friends whose fathers had also died. I invited them to write a short text about their fathers and paired each with one of the photographs, these appear together in the confidantes book. It became important to create the book in order to share their words, to take the work beyond my own father, beyond my own experience and offer the complexities we all experience in the death of a parent. Not all are easy, not all are joyful. And the ground upon which these complicated and poignant emotions, are everyday objects that wipe away tears, mop up scrapes and scratches and catch sneezes and coughs. The body fluids that seep and weep and make us human.

What kind of response have you been getting from people during the course of this exhibition? Do you find people are interested in sharing their personal narratives with you, because you are prepared to share your own with others?

The responses have been wonderful, and I’ve had some great discussions with people in the gallery. I’ve been holding a sewing circle in Gallery 2 each week, which has brought all kinds of conversations into the space. And this has also been an opportunity to meet visitors and answer their questions, and chat informally about the show. And yes, the confidantes evoke memories for many people I’ve spoken to. Someone shared a story with me about their grandfather, who migrated to Australia as a young man. He bought a sewing machine and began to make hankies. Her grandfather went on to establish Nile Industries, one of the cotton manufacturing companies that produced domestic textiles for several decades - sheets, towels, clothing AND hankies. She has a large collection of them.

What is your favourite and least favourite thing about being an artist?

It is an incredible privilege to have had an art education, to have worked as an artist for most of my adult life, in different capacities. Teaching, community projects, having shared studios with amazing people, artist residencies, running workshops. The wonderful solitude of a studio practice for thinking and making, and then the social connection with others in community and teaching.

Least favourite? Watching the erosion of tertiary education, the dismantling of skills-based learning through TAFE, when access to art should be available to everyone. And knowing it can be so much better.

What is a common thread between all your works and exhibitions?

I’m going to use a passage from an essay I wrote a few years ago for Garland magazine, which is about my practice.

‘The work of textiles and its connection to the human sits at the centre of my practice, in the language of material. Joining, wrapping, binding, stitching. Stringing things together, whether in thought or in material, manifests the tangible. Or sometimes the intangible. It isn’t always possible to know what is being made until it has been completed. Making, for me, is imagining. Making is propositional. The privilege of practice, of making, comes with the sense of responsibility to materials. When traces of the past are bound up in those materials, we behold the work of time. Consequently, in the time and space of the making process, that is, in the present, objects and materials are re-membered and imagined into the future. I gravitate to fragments, to the remains, to that which is left behind. I move back and forth and loop around, revisiting old works to begin new ones. The threads are there.’

Can you tell us a little about your writing practice and how it relates to object making?

Writing has always sat alongside my studio practice. I write as a way of thinking through ideas. Sometimes writing can spark ideas or lead me towards a work. Writing or fragments of writing might also appear within a work as text. Writing is a lot like drawing, the process of drawing. Again, it comes back to that place of not knowing, of just starting and letting the process take you. I am a huge fan of the writer, Rebecca Solnit and in particular, her book, The Field Guide to Getting Lost. It is one book I return to over and over again.

I love the relationship between words and objects, the play between language and art. The reciprocity in ‘reading’ images and creating images in words. I’ve often contemplated undertaking a writing course. Maybe that is next.

What is the most important aspect of your practice and can you explain to us why?

All of the above!

Is death and dying still a taboo subject and do you think things are changing?

I’d like to think that death and dying and the conversations around it have begun to shift. Tender Funerals is a great example of social change and just one of many quiet revolutions happening in the funeral industry. Jenny Briscoe-Hough and the Port Kembla Community Centre came together to make a change for their community, that was seven or eight years ago? And look at how this has progressed and grown. Tender Funerals Mid North Coast has been operating for a few years, Tender Funerals Canberra is about to open and there are communities all over Australia that have begun the process to establish a Tender Funerals in their city or town. It shows that the desire and need for transparency and connection is there. To not talk about it is to keep death cloaked in fear and ignorance.

At my mother’s funeral, her great-grandsons carried her coffin into the chapel. That image still makes me cry. These big boys she once carried as babies now carrying her. Jenny was our celebrant and afterwards, she said ‘this is how we do it, we bring the young ones in, give them responsibility and permission.’ Cultural change, one family at a time.

I have conversations all the time about death. I guess because it is something that has come close to me in the last ten years, it has become both subject matter and part of the work I do. The residency at Tender Funerals brought about a shift in my own practice. Goodness, I now run shroud making workshops! I made a one for my mother and while I could make them for others, I’m more interested in supporting people to do it for themselves.

Can I also mention that there is an open invitation for anyone to come along to the Tender Sewing Circle. We meet fortnightly on a Saturday afternoon in Port Kembla. It is a social space for friendship and support. We share skills and learn new projects, make stuff with recycled fabrics and do sewing for mortuary care.